The effectiveness of a CG system within a public regulatory framework relies in important ways on the ability of regulatory agencies to impose timely and effective mechanisms that serve not only to punish undesirable behaviour but that also work to correct it going forward and to send a clear signal to other persons in the market.

This section is concerned with the question of how regulatory agencies go about exercising their powers of enforcement in relation to instances of a failure in CG standards. Clearly there are two quite different levels to be considered: what one might for the purposes of this section call «discipline» where CG standards have been breached but which have not resulted in material damage to shareholders or market integrity, and «enforcement» where the failure to adhere to CG standards has been egregious and resulted in material damage to investors and/or the market. One might also add to that list the effectiveness of discipline or punishment serving to direct an issuer and its directors toward desired behaviour, i.e. by adopting and implementing better CG standards.

As regards discipline, the Exchanges in the United States and the SEHK have limited effective power over issuers, as discussed in Appendices I.1 and III.1. In the UK, disciplinary power rests with the FCA, not the Exchange, and is generally regarded as effective, not least because it has the power to impose fines in an unlimited amount in respect of breaches of the listing rules, which enables the FCA to transition between discipline and enforcement, as those terms are distinguished above.

The FCA and the MAS both have the ability to directly enforce the listing rules as a result of both jurisdictions giving statutory effect to the listing rules (for a discussion, see Section 3.6.1 «Information disclosures generally»). The FCA also has the power to direct an issuer to appoint a sponsor to advise the issuer on the application of listing rule requirements that the issuer is or may be in breach of (see Appendix II.6.4).

In contrast, the broad equivalent to listing rule enforcement in the United States is not driven by the listing rules per se but are brought within the scope of Federal securities law as a result of the Form S-K required annually by the SEC, the contents of which align with certain CG provisions of the listing requirements of the Exchanges. This, in effect, makes disclosure pursuant to the listing rules subject to section 10(b) of the 1934 Act and the SEC's Rule 10b-5, and Regulation FD. Bringing listing rules disclosures within these provisions are effective because they are actively enforced (see Appendices III.3.1 and III.6.4) and, consequently, the risk of liability drives the behaviour of persons responsible for making disclosures. Indeed, Rule 10b-5, which may be relied on by both the SEC and private litigants, has become one of the cornerstones of disclosure standards - and liability - for listed issuers and companies seeking to be listed.

While enforcement in the United States has traditionally rested with the SEC, in 2008 a new regulatory agency was established - the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The mandate of the CFPB is to protect consumers against unfair, deceptive, or abusive practices and take action against companies that break the law. Regulatory powers include monitoring, investigating, and enforcing the law. The CFPB may therefore take action in relation to breaches of legal requirements that overlap with the powers of the SEC.

In Singapore, enforcement of listing rules and the CG code rests primarily with the MAS, although the Exchanges in Mainland China also have the power to discipline (see Appendix IV.6.4). Similar to Hong Kong's comply and explain regime, prior to 2012, breaches of Singapore's CG Code were subject to lighter sanctions, such as reprimand and disqualifying directors, in comparison to the civil and criminal sanctions discussed above. Some questions had been raised concerning the effectiveness of the SGX's enforcement powers. The Asian Corporate Governance Association (ACGA) CG Watch 2014 asserted that Singapore had «less impressive progress on enforcement» (see Appendix V.1.3). This had been particularly evident with the CG Code's «comply or explain» regime with continued criticism in the media, acknowledged by the government (also in the media and in parliament) and the SGX through the announcement of a CG review into the matter (see Appendix V.1.3). However, since 2012 MAS has been given the power to make rules, and is probably more efficient in setting and enforcing standards than in Hong Kong. In 2015, after extensive consultation, the SGX established Listing Disciplinary and Listing Appeals Committees. The consultation also resulted in strengthening the listing enforcement framework with Chapter 14 of SGX listing rules added on 7 Oct 2015. The SGX's enforcement powers were also strengthened. The MAS also has administrative penalty powers (see Appendix V.6.5). Sanctions are mainly confined to administrative actions because of a fragmented regulatory structure, and enforcement by way of criminal proceedings is rare - criminal proceedings can only be undertaken by Commercial Affairs Department (CAD) with MAS and the SGX being constrained to administrative-sanctioning powers and limited powers of investigation.

In Mainland China, enforcement of listing rules and the CG code rests primarily with the CSRC. While CSRC has the power of enforcement, political interference and lack of resources have meant that CG standards in Mainland China remain strong on paper but weak in practice. There are a number of key differences between the enforcement of CG standards in Mainland China and Hong Kong. First, the CG Code and standards in Mainland China are enforced by the CSRC, not the exchanges. Second, the requirements in the CG Code in Mainland China are mandatory, whereas in Hong Kong the CG Code is subject to a «comply or explain» regime. Third, the sanctions imposed by CSRC are more extensive than those of the HKEX. This gives the CSRC a wider range of options to ensure that the Code is effective in its operation and therefore maintain CG standards. In terms of system design, this is perhaps a stronger enforcement system than found in Hong Kong.

The MAS and CSRC have the power to enforce but due to heavy government influence have been unable to do so. There is no such government influence in Hong Kong, however, the SFC is unable to directly enforce listing rules and the HK CG Code - its powers of oversight of the listed market are limited to those given to it under the SMLR. The lesson from Singapore and Mainland China is that, to be effective, SFC may need to be given similar powers to enforce CG standards.

Hong Kong

No one regulatory body is charged with the enforcement of CG standards in Hong Kong, although each of the relevant regulatory bodies do undertake enforcement actions within their scope of authority. As discussed in Section 3.1.2 «Trends in regulating CG standards», and Appendices I.6 and II.6, the powers of the SFC are in important ways limited in respect of the setting and enforcement of CG standards as compared to the FCA. Neither the SFC nor the SEHK have any power to fine in relation to breaches of the listing rules including its disclosure requirements. The disciplinary powers of the SEHK are widely regarded as toothless. Only if the breaches are egregious and amount to oppression, defalcation, fraud, misfeasance or unfair prejudice for the purposes of section 214 of the SFO does the SFC have the power to seek a more severe enforcement mechanism. The SFC does have specific powers under SMLR, which may also be invoked in respect of more egregious breaches.

Specific CG standards established by the listing rules are enforced by the SEHK, or the SFC if the breach involves provisions in the SFO, the former giving way to the latter where the SFC proposes to take legal action. The SFC has no disciplinary powers over listed issuer's CG standards per se but is empowered to take action where the issuer has breached a provision of the SFO, such as sections 277 or 298, or CWUMPO, however, the relative lack of enforcement actions under these provisions (there have been none under CWUMPO) means that the perceived risk of liability does little to affect behaviour, Instead, the system in Hong Kong that traditionally has brought consequences to misВ¬disclosure tends to be commercial in nature (e.g. de-listing followed by winding up), or the application of sanctions either by the SEHK under the listing rules, which is comparatively weak, or by the SFC against the persons (such as sponsors) it regulates. There is some sign that this is changing as the SFC have started to become active in relation to items sections 277/298 and Part XIVA of the SFO. As already noted in Section 3.6.1 «Information disclosures generally», the SFO does provide for civil liability but there have been no actions taken under the relevant sections.

Standards of financial disclosure are subject to the same considerations, although the situation is currently in a state of flux as regards the split of functions between the HKICPA and the FRC and how the powers of the latter will be finally defined.

A positive development in this regard was the removal of the price-sensitive information provisions of MBLR 13.09 (as it was) and the introduction of Part XIVA of the SFO in 2013. This empowered the SFC to seek fines through the MMT, and extended the powers of enforcement to officers of the issuer and not just the company. It also enabled a person who has suffered loss as a result of the breach to bring a civil action for damages through the courts. While this in some ways is similar to UK, an enforcement action by the SFC must be undertaken through the MMT, not by the regulator directly as in the UK, thus introducing not only a significant delay in the timeliness of enforcement but also the cost of doing so. Moreover, the fining power of the MMT is limited to HK$8 million in contrast to the FCA's power to impose a fine in an unlimited amount. In Hong Kong the enforcement of information disclosures in the markets, an important feature of an effective CG system, in important ways does not rest primarily with the regulators, their role instead being restricted to oversight and the commencement of enforcement actions undertaken in the MMT. The dissemination of false or misleading information by an issuer might also fall to be treated as market abuse - whereas the FCA has similar fining powers the SFC would need to make an application to the MMT or the court depending on which provision of the SFO is being relied on.

Discussion

As the powers given to regulators in Hong Kong are generally inferior to their international counterparts, this gives rise to a fairly obvious suggestion that these powers should be increased to be on par with international norms. What has been done in relation to the removal of parts of listing rule 13.09 to create Part XIVA of the SFO could be regarded as a step in that direction but only a partial one since the change represents only a subset of other important disclosures (and rights) that are to be provided to shareholders under the listing rules, and because the SFC did not acquire the administrative power to fine (it has to apply to the MMT).

The foregoing considerations give rise to two separate topics: (1) the potential role of the SFC as an enforcer of the listing rules, and (2) whether the SFC is the only entity that should be regarded as an enforcement body. These will be dealt with in turn below, and each give rise to recommendations. The final part of this section turns to a third topic related to this discussion: (3) the existing powers of the SEHK.

(1) The potential role of the SFC as an enforcer of the listing rules

The enforcement of the listing rules in Hong Kong stands in high contrast to the powers of regulators in the other jurisdictions studied. It would not be a new idea to suggest that the SFC be given the power to fine listed issuers for breaches of the listing rules, nor that certain parts of the listing rules (such as Chapters 4, 14 and 14A) be removed to statute. This has been proposed before, notably in the FSTB and SFC consultations on proposals to give statutory backing to major listing requirements issued between 2003 and 2005, as discussed in Appendix I.2.1. However, the proposals were rejected. HKEX at that time was supportive of statutory backing for the more important listing rule requirements as proposed in the Consultation Conclusions on Proposals to Enhance the Regulation of Listing, however, it disagreed with the details of the implementation of the same as proposed by the FSTB and the SFC. The proposals have also given rise to considerable controversy and pushback from the industry. Contemporary discussion in relation to listing reform remains positioned around and to a large extent pinioned by these consultations.

The fining powers of the SFC are broadly similar to those possessed by the SEC, which also does not enjoy the outright power to fine possessed by the FCA. (The SFC only has a power to directly fine in respect of persons who are subject to its regulatory oversight under the SFO.) This reflects the fundamental nature of the developments in the UK toward a statutory basis for listing regulation. Accordingly, any discussion that suggests the SFC be given a power to fine would need to be based on a more fundamental discussion of regulatory architecture of the oversight of listed issuers, and would need to be properly embedded in a wider legal framework. Certainly, giving the SFC the power to fine listed issuers - or, more pointedly, their directors - would require significant consideration and any proposal would be controversial. Any proposal in this regard would need to be established on a basis that better addresses the concerns expressed in the previous consultation exercise. This might incorporate, for example, mechanisms for regulatory collaboration as to the imposition of fines that involves not only the SFC but also the practitioner-driven Listing Committee of the SEHK in order to ensure appropriate checks and balances in relation to the imposition of fines, subject to appropriate appeal mechanisms such as are already in place in relation to the specified decisions of the SFC that may be appealed to the Securities and Futures Appeals Tribunal. It would need to be measured against an assessment of whether the powers under the current system of enforcement are adequate to its purposes. This would need to take into account not only factors related to the effectiveness of deterrence, such as the consequences of delayed sanctions, but also the resource based capability of the enforcement mechanisms, such as the resources of the MMT and the regulators. Accordingly, further investigation would be needed before a clear proposal could be made that the SFC be given administrative fining power over listed issuers and their directors.

Since the UK introduced a listing authority, there have been intermittent calls for Hong Kong to create a listing authority, as was proposed in the report of the Expert Group in 2003. However, it is suggested that in the absence of a review of the significant changes to the Hong Kong market since 2003, repeating such a call appears premature. Moreover, it is far from certain whether an alternative statutory model would have worked better than the current model under which Hong Kong has enjoyed a considerable measure of prosperity. As noted elsewhere, the introduction of the statutory model in the UK was paired with significant structural changes that had a clear mandate from Parliament and was accepted by the market, but also generated a series of complex and ongoing changes that has left the UK system being regarded by some as overly complex.

Given the recent difficulties in progressing listing reform as proposed by the SFC and HKEX, and the lack of direction from the government on the question, it is difficult to recommend, given the purposes and orientation of the present study, that a sweeping change to regulatory architecture be undertaken. However, within this study's scope it is nevertheless possible to make three different types of suggestion, the first working entirely within existing regulations, the second representing a modification to the SMLR that may benefit issuers and shareholders, and the third is based on relevant developments since 2003.

First, working within existing regulations:

The SFC and the SEHK have powers they do not appear to fully utilize (the position of the SEHK's powers in this regard are discussed under (3) below). There is some parsimony in a suggestion that the regulators could seek to use existing powers more effectively to bring improvements to CG standards. While this may not amount to a significant-looking suggestion, for example as compared to suggesting that the SFC be given the administrative power to fine, it is one that has the considerable benefit of being able to be immediately implemented and one that allows another enforcement focus to be shone on the topic of CG standards.

The SFC already has regulatory oversight of the listing application process and the ongoing disclosures and listed status of listed issuers - this is provided for by the dual filing regime and the powers given to the SFC under the SMLR. However, those powers are somewhat blunt instruments, being: to object to a listing or to indicate it does not object subject to the satisfaction of conditions it specifies, to direct the SEHK to suspend all dealings in an issuer's securities and to impose conditions on the suspension being lifted, or direct the cancellation of an issuer's listing. These powers only arise in specific circumstances (as discussed in Appendix I.3.2) that do not cover breaches of the listing rules per se save in relation to listing applications.

Once the SFC has directed a suspension under one of the routes provided for, the SFC has corresponding powers under section 9(4) of the SMLR to direct dealings to recommence subject to conditions that it might impose (the power of the SEHK to impose resumption conditions is discussed under (3) below). Where the suspension has been invoked on the grounds of maintaining an orderly and fair market or protecting investors, the SFC has the discretion to impose such conditions it considers appropriate to address the relevant issue. While the SFC is required to consider any representations made by the SEHK or the issuer, where no representations are made it may nevertheless exercise the power to direct resumption of trading subject to conditions being met.

Here it seems possible that, if the problem has arisen out of the issuer's CG standards or processes, such conditions could be used to address those CG shortcomings. For example, the SFC could require changes to a board's processes, including the functioning of the board's sub-committees, that reduce the likelihood of a recurrence of the problem and that may serve to catalyze change. Bringing a focus to an issuer's CG standards, systems and processes (particularly those that relate to internal controls and disclosure cum transparency) would be consistent with a more progressive approach to regulation that looks to solving underlying problems as opposed to merely addressing instances. The use of such catalyzing conditions recognizes, and must be premised on, the reality that certain shortcomings of listed issuers arise out of a CG culture that is not in keeping with the minimum standards expected by the market. However, some care would need to be taken to ensure that such conditions do not result in rewriting the listing rules for some issuers so as to create an uneven playing field. Where this concern arises, it may be able to be addressed by way of placing a time limit on compliance with the condition that gives an opportunity for catalysis to take hold. Catalyzing conditions might also be paired with requiring the appointment of a compliance adviser for the relevant period. The potential range and use of such catalyzing conditions would require further detailed examination, as does the precursors required before the SFC might use them. If correctly developed, catalyzing conditions can work toward two ends: (1) to direct an issuer toward better CG standards, and (2) to more openly promote the SFC's policy attitudes toward good CG. Item (2) is an important alternative to negotiations that might otherwise take place in private.

In relation to listing applications, such conditions conceivably could address CG shortcomings in the listing applicant's governance arrangements.

The foregoing leads to Recommendation A4.6.2 «SFC to develop use of conditions when exercising existing SMLR powers».

The foregoing recommendation can be read together with recommendations made elsewhere in this study that propose giving a degree of power to the SFC in a manner that does not require changes to legislation or the dual responsibilities model, namely, Recommendation A4.5.1 «Legal status of CG disclosures», and Recommendation C4.5.2 «Status of listing rule compliance and related disclosures (continuing)», both of which bring certain CG disclosures made by listed issuers pursuant to the listing rules within the scope of the existing provisions of the SFO.

A problem in practice with imposing conditions on suspended issuers arises where its directors may be content to leave the company in a suspended status despite the potential prejudice to minority shareholders. This problem is addressed by Recommendation A4.6.3 «Calibrate SFC's powers under the SMLR», discussed next.

Second, modifying the SMLR:

To deal with the enforcement gap, the SFC has increasingly looked to ex post enforcement mechanisms through the courts. This is expensive and time consuming, and it is not certain that such actions will always benefit investors who have suffered loss. The exercise of the SFC's power under the SMLR to suspend an issuer's listing, while striving to protect the market and its investors, nevertheless has the effect of shutting shareholders out from being able to trade risk. Suspension is an all-or-nothing action that lacks gradation. The SEHK's Listing Committee has noted its concerns regarding the number and duration of suspended companies, including some of which remain suspended for long periods. During the period of suspension, in the absence of correcting the fault and seeking readmission to listing, the issuer sits in limbo that leaves the SEHK with only one option - delisting - or the SFC may decide to devote resources to investigating for evidence of wrongdoing sufficiently egregious that would warrant bringing a matter before the MMT or a court.

The SFC's oversight powers under the SMLR can also be developed within the existing regulatory framework by giving the SFC more nuanced powers that sit within the scope of - and in that sense do not extend - its existing powers under the SMLR. Providing the SFC with limited alternative powers that serve as a warning-cum-precursor to suspension and that redirect errant behaviour may create a preferential outcome for the issuer, its investors, and the market. As an alternative to suspension, providing for a fine that works as a warning-cum-precursor to suspension might provide a «win-win-win» for the issuer, its investors and the market as opposed to outright suspension. The power would need to be premised on the same grounds as its existing SMLR powers and provide for a fine together with the imposition of conditions on the issuer and/or its officers in lieu of suspension but without prejudice to the SFC's power to suspend where the conditions are not satisfied. More mundane breaches of listing rules that do not impact on the public market per se should not give rise to the SFC's power to fine. In keeping with the dual responsibilities model, it would be appropriate to require the SFC to consult with the Listing Committee prior to imposing a fine. To maintain regulatory efficiency, the power should be exercisable by the SFC directly, and be classified as a specified decision appealable to the SFAT. This proposal might avoid the problems of previous proposals to give the SFC a disciplinary fining power in respect of breaches of the listing rules more generally.

The power to fine could also be supplemented by giving the SFC power to issue a formal caution where the SFC is of the opinion that there have been material breaches of the listing rules that, if left unchecked, could lead to it exercising its power to fine and/or direct a suspension of trading.

Imposing a fine with conditions in lieu of directing a suspension is analogous to section 201(3) of the SFO, which contemplates (in the context of intermediary discipline) the SFC reaching an agreement with the intermediary as to what power or other action it will exercise. This provides the intermediary and the SFC with alternative means of discipline that represents a preferred win-win outcome. It would be possible to adjust the SMLR to also provide for such a negotiated enforcement action.

However, the imposition of conditions or seeking negotiated enforcement might not work where directors of an issuer may be content to leave the issuer in a suspended status indefinitely despite the possible prejudice to minority shareholders. Accordingly, where the directors do not take steps to meet the conditions or negotiate an enforcement penalty, it may be appropriate to devise a mechanism whereby shareholders get to decide. Given the company's basic premise that it is a publicly traded company, and that a suspension fundamentally affects that premise, it would be appropriate for the conditions and/or the proposed enforcement to be put to shareholders in a general meeting. Directors and any controlling shareholder and their associates would need to be prohibited from voting. It is suggested that the imposition of a cold shoulder order on the directors and any controlling shareholder and their associates until such time as the shareholders have voted would be an effective mechanism of procuring the matter being brought to the shareholders.

The foregoing leads to Recommendation A4.6.3 «Calibrate SFC's powers under the SMLR».

Third, as regards relevant developments since 2003:

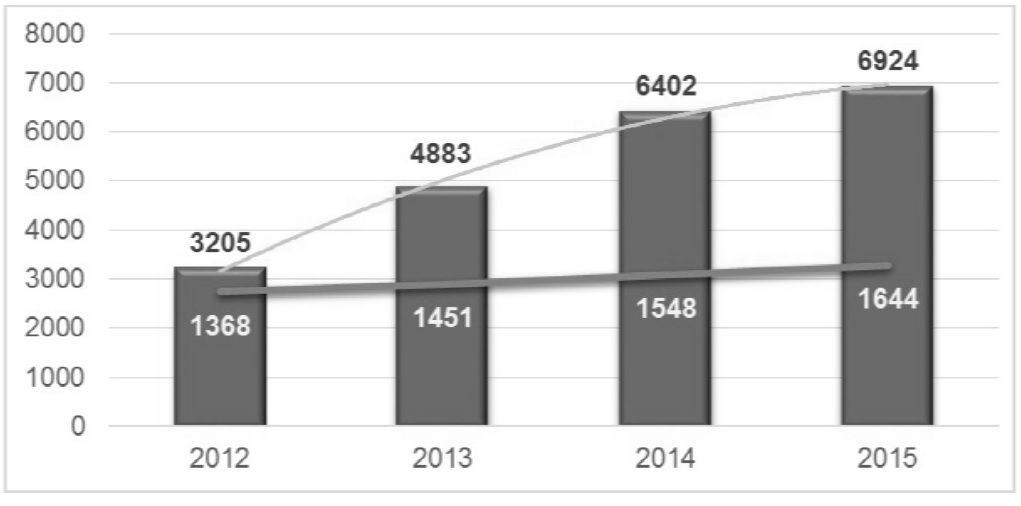

The major evolution of the SFC's oversight of the listed market has been the powers given to by the introduction of Part XIVA of the SFO in 2013, which deals with the disclosure of inside information. This was a statutory codification of the previous provisions of MBLR 13.09 concerning the disclosure of price sensitive information. This appears to have been successful in promoting overall transparency in the market despite its relatively short track record. Evidence suggests that the number of inside information disclosures being made has increased following Part XIVA coming into effect, by 52.4% and 31.1% in 2013 and 2014 respectively, as shown in the Diagram below.

Number of inside information announcements

In addition, the SFC have to date brought three successful actions under Part XIVA concerning late disclosure, which have resulted in fines against the issuer and its senior executives, cost orders and director disqualification orders. It is also possible that, in serious cases, the SFC may consider taking action under section 213 of the SFO.

The generally successful experience with Part XIVA is relevant to note in relation to earlier, failed, proposals to give other parts of the listing rules statutory effect, namely MBLR Chapter 4 concerning periodic financial reporting, and those aspects of MBLR Chapters 14 and 14A concerned with shareholder approval of notifiable and connected transactions.

Hong Kong has not been without its share of problematic listings that have involved financial mis-disclosure. The increasing predominance of Mainland Chinese businesses on the SEHK is of particular relevance in view of investigations undertaken by the SEC around the time of cautionary reports were issued by Moody's and the New York Times - in each case relating to Mainland issuers - and a number of cases where that concern has materialized.

The difficulty experienced by the MMT in the CITIC case (see the discussion of it in Section 3.7.2 «Policy development agencies») perhaps also highlights the need to provide clearer, law-based provisions to govern transactions that otherwise provide to wrongdoers avenues of shareholder abuse - as the events in CITIC occurred prior to the introduction of Part XIVA it can be noted that the case would have been decided differently had Part XIVA been in place at the time and, if so, this may have led to the compensation of investor losses.

Some further support for a statutory approach may be found from the experience in the United States, where significant and/or connected transactions have been the subject of many court cases (Delaware), and this has led to a higher level of caution being exercised by directors. On this basis it might be argued that statutory codification would not be necessary if an adequate body of case law was developed in Hong Kong. However, the experience in Delaware has also been the complexity of ever-developing case law and the consequential difficulty of forecasting the attitude of the court in relation to new cases. By way illustrating this, in a note to clients in 2014, Gibson Dunn listed out eleven different non-definitive scenarios expected to be relevant to the likely standard of review applicable in a Delaware M&A transaction to determine whether directors have complied with their fiduciary duties. This complexity gives rise to an increased uncertainty and so too the cost of doing business.

This positions statutory development as an option that may better serve to foster corporate transparency, shareholder involvement and director accountability insofar as it may provide greater certainty to both managers and owners alike.

While this study has not derived sufficient evidence to lead to a recommendation that certain listing rules now be given statutory support, based on what has been observed in the other jurisdictions studied and the Part XIVA experience, it is suggested that the ground conditions have sufficiently changed for this discussion to be re-examined. In doing so, the dangers of treading over old issues must be in the forefront of considerations, in particular, as to whether there is sufficient market consensus to warrant undertaking a new public consultation.

The foregoing leads to Recommendation A4.6.4 «Statutory backing of certain listing rules».

As already noted in Section 3.6.2 «Listing rules» the above recommendation may be contrasted with the proposal to make shareholders third party beneficiaries of the contract between the SEHK and the issuer, which would not require any change to legislation and which could be more simply implemented with the involvement of the SEHK and the SFC. Both recommendations address a main theme of creating more effective means of legal recourse over the listing rules, whether by creating powers in the hands of the SFC, shareholders, or both.

For a discussion of issues related to the above, see also Section 3.3.4 «Audit committee» and Section 3.7.5 «Duties of directors».

(2) Whether the SFC is the only entity that should be regarded as an enforcement body

As the CFPB's mandate has no equivalent in Hong Kong, is there a case for proposing one albeit limited to CG related concerns?

Structurally, the SFC sits in a similar position of enforcement as does the SEC. Among the SFC's statutory objectives is the protection of members of the public investing in or holding financial products. Although powers of the SFC may be exercised in a way that has a similar effect in protecting investors, this is not the SFC's sole mandate (see Appendix I.4.1). As already mentioned in Section 3.7.1 «Impact of regulatory design», the SFC is now increasing its focus on corporate fraud and misfeasance in its enforcement. While this is hoped to raise the risk of liability, and hence standards, it will directly benefit shareholders where the SFC is able to obtain compensation orders under section 213 of the SFO, and indirectly benefit them where similar orders are obtained against directors in favour of the company under section 214 of the SFO. The SFC has also sought to bring greater focus to the role of the sponsor in bringing new companies to the listed market, though has demurred from recommending changes to the law that would be necessary to enable investors to bring a civil claim against sponsors. Following the Lehman Brothers Minibond crisis, the SFC was able to negotiate substantial recoveries for investors who had suffered loss.

However, the SFC has other obligations and considerations that may in its detail compete with specific instances of consumer interests, including in relation to market integrity, facilitating innovation and competitiveness, and the duty to make efficient use of its resources. The SFC's decision not to appeal the MMT's finding in the CITIC case, discussed in Section 3.7.2 «Policy development agencies», may be an example of this. The SFC was designed to regulate the public markets, not to act as an advocate for shareholders. The SFC does not operate any department or division that is solely concerned with the interests of investors, it being notable that its Enforcement Division when taken as a whole deals with a variety of matters. As such, when considering the interests of shareholder's in specific situations, the SFC is not an unconflicted agency.

In 2012 the Financial Dispute Resolution Centre (FDRC) was established. Though the FDRC is not concerned with issues related to CG (its terms of reference are disputes with licensed corporations and authorized institutions) it is relevant to note as it does represent an attempt to establish a better means of enabling consumers to seek redress. However, the FDRC has not been successful.

One other consideration of relevance to this discussion is the absence of collective redress in Hong Kong. Although the SFO creates rights to bring civil actions for damages in respect of corporate mis-disclosure, it is very expensive for an individual to do so, and no claims under these provisions are in fact brought, rendering the provisions in some ways a lame duck. The absence of collective redress, the cultural leaning toward the regulator to take action, and the range of considerations that the SFC needs to take into account before commencing any action within its power, are in fact highly interrelated.

This suggests there may be value in exploring whether some form of agency equivalent to the CFPB might be established with a specific mandate to enforce shareholder rights. Creating a new statutory body is complex and requires careful consideration of, inter alia, its objectives, powers, accountability, governance, staffing and funding. Such an agency would need to be empowered to bring an action for the benefit of shareholders, for example, by amending sections 213 and 214 of the SFO to provide that such agency, and not only the SFC, may bring an action. Powers of investigation and evidence collection would also need to be provided for.

It would be neither necessary nor desirable that the powers of the SFC would be affected by such an agency - they would remain unchanged, although the new agency might reduce the enforcement burden of the SFC. Nevertheless, creating an agency with powers that overlap those of the SFC might be perceived by the SFC as a challenge to their authority in relation to certain powers they presently enjoy exclusively, although this would seem an inappropriate reaction if both agencies were working toward the same objectives of market integrity and investor protection. It may also be perceived by the market as an overlap with the SFC's function, causing confusion in the market as to who is responsible for enforcement. These considerations may be addressed by MoUs, as already utilized by the SFC and other regulatory bodies with overlapping responsibilities, such as the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, that makes it clear that the SFC remains the industry regulator and details how the two agencies are to coordinate enforcement actions in which both have an interest.

The proposal to establish a new enforcement agency is likely to be met with resistance from the market as it represents an increased liability risk. The absence of a very clear mandate from the market will present implementation challenges. However, as discussed in Section 3.5 «Equality» and Recommendation E4.9.3 «Market development», the longer-term priorities of market development should be repositioned around more fundamental objectives. While potential resistance to the proposal from market participants is a material consideration, the primary question is whether the proposal, if correctly implemented, would operate to further CG standards in Hong Kong in a manner that facilitates long-term market development.

The foregoing leads to Recommendation E4.8.2 «Establish an investor protection agency».

Alternatively, the suggestion was made in Section 3.7.2 «Policy development agencies» that the SFC establish a new division or functionality that has as its focus CG and the interests of shareholders - that led to Recommendation E4.8.1 «Establish a CG Unit and CG Group». While not directly concerning enforcement per se, such a functionality may assist in the development of more effective enforcement choices that benefit consumers in relation to failings of CG standards.

(3) The existing powers of the SEHK

The SEHK has the power under MBLR 2A.09(10) to require issuers to «take, or refrain from taking, such other action as it thinks fit». A similar provision has been used by powers of the Takeovers and Mergers Panel under the Code on Takeovers and Mergers, which provides that the Panel may impose sanctions «requiring further action to be taken as the Panel thinks fit». This power has been used to require a person who breached the Code to compensate investors. Although the Panel's ruling had been subjected to an application for judicial review, eventually leading to the Privy Council, the Panel's use of its power in this regard stood.

In addition, where an issuer has been suspended, the SEHK has the power «to impose such conditions as it considers appropriate» on the resumption of trading.

There are various ways the SEHK could use such powers to direct an issuer or its directors toward improved CG standards. Whereas the leverage available to the Panel that gave its order effect in practice was its ability to issue a cold shoulder order, the primary leverage available to the SEHK would be its power, exercised via its Listing Committee, to suspend or continue the suspension of trading, or cancel a listing. These powers could also be used with effect, for example, to require an issuer and/or the relevant director(s) to make a statement as to what measures will be undertaken to ensure non-recurrence of this or similar breaches, and to subsequently report on implementation. This would be consistent with the approach proposed by the HKEX in its current proposal for suspended issuers to give quarterly updates on satisfying resumption conditions - the primary issue is what conditions are appropriate to impose. Such statements could also be required to be reiterated in the annual report and/or on the next occasion the shareholders are asked to re-appoint the relevant director. This may be a more effective means of activating reputational liability than a mere censure and could go a long way to introducing discipline that works proactively to bring about improvements in an issuer's CG practices. Given there is no self-reporting requirement in the listing rules (although see the discussion in Section 3.3.2 «Disclosure of listing rule compliance» which leads to Recommendation C4.5.2 «Status of listing rule compliance and related disclosures (continuing)»), the SEHK could adopt a policy via a guidance letter that if a breach of the listing rules is self-reported upon it coming to knowledge of a director, then the SEHK would not impose such a sanction. It is further suggested that the imposition of such a sanction may be well attuned to the Asian culture, including as regards the large number of Mainland enterprises listed on the exchange who may place a high value on their personal reputation. In this regard it might also be noted that directors of issuers listed on the Mainland China Exchanges are subject to annual self-critiques, albeit those are frequently little more than cut and paste exercises. The foregoing is merely one example of how the power could be used more effectively - other such uses of the power could be set out in a guidance letter on a nonВ¬binding basis.

While these powers are ostensibly quite wide, it would be important to ensure that the use of the powers remains within the scope of the contractual relationship between the issuer and the SEHK.

The foregoing leads to Recommendation C4.6.1 «SEHK to develop use of existing disciplinary power».