3.8 It is a continuing challenge for reporters and commercial organisations to understand their obligations and apply the law correctly. To assist with compliance with reporting obligations reporters may consult guidance. Whilst some of this guidance is approved by HM Treasury, and must be taken into account by a court, it does not ultimately have the force of the law. At present, reporters carry the risk of individual criminal liability. They must identify their obligations from a complex legislative scheme and multiple sources of information offering guidance on the law.

3.9 In the Consultation Paper we made several observations about the way in which guidance has evolved:

(1) the large number of documents produced by various parts of the regulated sector and law enforcement agencies suggest a clear demand for guidance;

(2) individual sectors may benefit from guidance which gives examples and assistance specific to the relevant business practices;

(3) it is counter-productive and inefficient to have multiple interpretations of the law across several different documents;

(4) not all of the available guidance is consistent and different sectors may receive contradictory advice on the application of the law. This leaves reporters exposed to a greater risk of committing a criminal offence.

Fragmented guidance

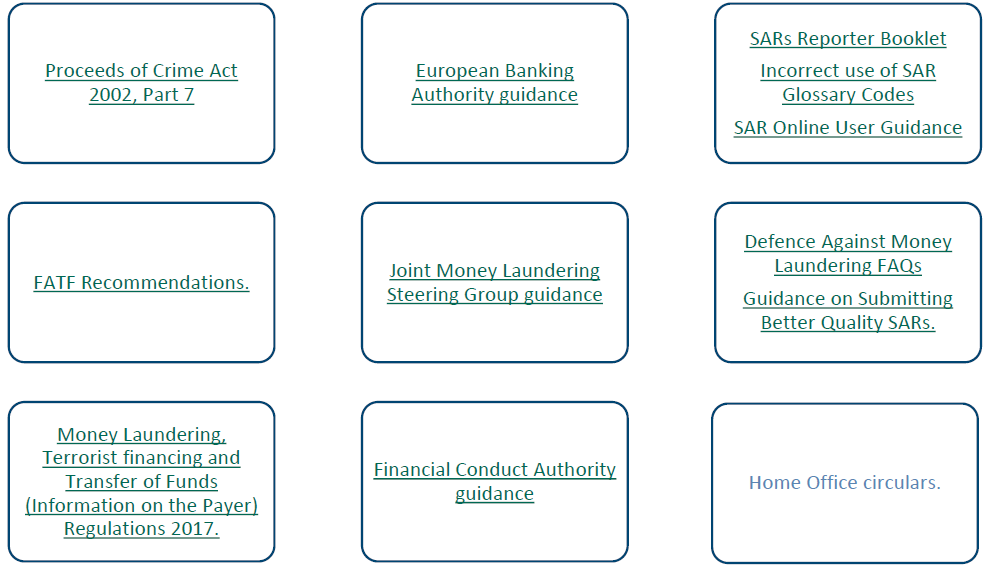

3.10 Guidance should support those working in the reporting sector and aid understanding of their legal obligations under Part 7 of POCA. However, the lack of a single authoritative text to supplement Part 7 has resulted in a number of different sources of guidance on fundamental legal concepts within POCA that are common to all sectors. For example, a nominated officer in a bank would need to consult a number of sources in order to comply with their obligations under POCA. There is scope for consolidation or rationalisation of some of these sources of information into a single source of guidance on the law, in particular on important legal concepts which apply across all sectors.

Example: potential sources of law & guidance for a nominated officer of a credit institution:

Conflicting guidance

3.11 Requiring every different segment of the reporting sector to consult multiple information sources to clarify their obligations presents obvious challenges and is burdensome. Furthermore, guidance issued by each sector does not, in this context, demonstrate a common understanding of important legal terms, concepts and exemptions/defences within POCA.

3.12 Some guidance is produced by those with supervisory or regulatory responsibilities (for example the Legal Sector Affinity Group («LSAG»)). Some of it is produced by trade associations or representative bodies (for example, the Joint Money Laundering Steering Group («JMLSG»)). Different sectors may diverge in how they interpret the legal obligations on a reporter working within their sector. They may offer different guidance on fundamental legal concepts.

3.13 Following the 2017 Money Laundering Regulations HM Treasury announced its intention to work with supervisors and industry to approve one set of guidance per sector. This is a welcome effort to harmonise these sources of guidance, rather than having multiple sources of guidance within an individual sector. For example, there is now one guidance document for the legal sector and one for the accounting sector. This is a positive step, but does not go far enough. There remains a strong argument for having a single, accessible, interpretation of universal legal concepts common to all sectors.

3.14 Examples of a lack of uniformity across approved guidance still exist, some of which we highlighted in our Consultation Paper. In relation to the application of the fundamentally important concept of suspicion for example, JMLSG guidance states:

Suspicion is more subjective [than knowledge] and falls short of proof based on firm evidence. Suspicion has been defined by the courts as being beyond mere speculation and based on some foundation, for example «A degree of satisfaction and not necessarily amounting to belief but at least extending beyond speculation as to whether an event has occurred or not», and «Although the creation of suspicion requires a lesser factual basis than the creation of a belief, it must nonetheless be built upon some foundation».

3.15 LSAG Guidance states that «there is no requirement for the suspicion to be clearly or firmly grounded on specific fact» and adds, «you do not have to have evidence that money laundering is taking place to have suspicion».

3.16 The Consultative Committee of Accounting Bodies («CCAB») counsels against «speculative» SARs and gives examples of disclosures which lack «specific supporting information». The CCAB also makes observations as to what a suspicion is and in doing so it uses similar terminology to the legal and accounting sectors. However, it also use additional phrases including «more than mere idle wondering», «a positive feeling of actual apprehension or mistrust» and «a slight opinion, without sufficient evidence». Whilst the phrases are designed to assist reporters, they may create confusion or complication.

3.17 The practice of individual sectors placing a gloss on legal terms embedded in guidance which are meant to be interpreted generically creates difficulties in practice. Our data analysis certainly suggests significant variation in understanding; stakeholders' application of the concept of suspicion varied substantially.

3.18 HM Treasury has confirmed to us that when approving guidance it does not insist that each supervisory body uses precisely the same terminology . There is clear merit in allowing each supervisory body to tailor its approach to the different challenges each sector faces in complying with the obligations under POCA. However, even small differences in terminology can impact significantly on how reporters apply the regime and can be responsible for creating additional confusion and inconsistency across different reporting sectors. Were it the practice of Crown Court judges to direct juries on the concept of suspicion in criminal trials across the country in such a way, it would create confusion and risk producing inconsistent verdicts. Where a reporter is at risk of committing a criminal offence and the subject of a disclosure can be denied access to their bank account, divergence on such fundamental terms in published guidance creates potential unfairness.

Insufficient collaboration in creating and maintaining guidance

3.19 Where guidance is drafted by a supervisory or trade body for the benefit of its members, it is unclear to what extent, if any, guidance produced for other sectors is considered and reconciled within it. In addition, there are currently limited mechanisms for law enforcement agencies to have direct input into the creation and updating of guidance in any systematic way. It may very well be that law enforcement agencies take a different view on how the law is interpreted and what information or intelligence is valuable. Consultation with the law enforcement agencies seems vital when such guidance is being constructed or updated if it is to be of maximum benefit to the relevant users, subject to ensuring that such guidance accurately reflects the current law. Inconsistency also arises between sectors, with some sectors providing this information in their disclosures to the UKFIU and others failing to do so, understandably relying on guidance issued by their supervisor. This presents real challenges in practice.

3.20 Key concepts within POCA are interpreted differently in sector-specific guidance. These interpretations do not always match with the views of law enforcement agencies. For instance, section 338 of POCA provides a defence of reasonable excuse. The CCAB anticipates that such a defence will only be made out in extreme circumstances such as duress or threats to safety. By comparison, the LSAG takes a more pragmatic view on useful intelligence. For example, LSAG guidance advises that the defence will be available to those who fail to make a disclosure where the only information that a reporter would be providing would be entirely within the public domain. In our discussions with law enforcement agencies, however, disclosure was considered to be crucial in these circumstances. This lack of clarity about when an offence may be committed fails to provide the reporters with the information that they need to avoid criminal liability.

3.21 Consultation is, of course, a two-way process. There are examples of key policy changes taken by the UKFIU which have been implemented by way of non-statutory guidance without formal consultation or oversight with the sectors. For example, in July 2016 a decision was taken by the UKFIU to rename the grant of appropriate consent as a ‘Defence Against Money Laundering' («DAML») or a ‘Defence Against Terrorist Financing' («DATF»). There has been no legislative change to reflect this and arguably, a fragmented approach to guidance risks confusion for those concerned with complying with their legal obligations.

No legal protection for reporters («safe harbour»)

3.22 While sector-specific guidance can be amended and updated, its non-statutory basis limits its usefulness. The courts are only permitted to «consider» any relevant guidance. Moreover, compliance with it does not, in itself, provide reporters with a defence to a criminal charge. Although it may be advisable, individuals are not bound to follow or apply guidance.

Conclusion

3.23 In the Consultation Paper, we provisionally concluded that statutory guidance would be the optimal way to resolve the issues of fragmentation and conflict. It could also provide greater legal protection for reporters. Further, consultation across all of the stakeholder groups could still be achieved by this method.

3.24 We provisionally proposed that POCA be amended to include an obligation that the Secretary of State produce guidance (subject to adequate consultation) on the following topics:

(1) the suspicion threshold;

(2) what may amount to a reasonable excuse not to make a required and/or an authorised disclosure under Part 7 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002;

(3) the process of making an authorised disclosure and the concept of appropriate consent.

3.25 We will discuss each of these matters in the relevant chapter below. However, in the next section we focus on consultees' responses to our provisional proposal that, in principle, statutory guidance is the optimal approach. We also analyse the best approach to drafting and issuing statutory guidance and consider how it might be created before making our final recommendations.